Download the whole case study as a PDF file (508KB)

Ayesha is an older British Asian woman who has some physical health concerns. She is a widow and lives with her son, Bilal. There are concerns that Ayesha may be experiencing coercive control from Bilal; a pattern which repeats Ayesha’s experience with her husband who is now deceased.

This case study considers issues around working with Asian communities, specifically Pakistani Asian women; cultural capability; reflecting on the values and knowledge that we bring to situations, and working with older victims of domestic abuse.

When you have looked at the materials for the case study and considered these topics, you can use the critical reflection tool and the action planning tool to consider your own practice.

Case details

Download the case details as a PDF file (413KB)

Ayesha, 66, was born in Pakistan and came to the UK with her husband, Tariq. She was 18, he was 28. They have four children and seven grandchildren. During their marriage Tariq was physically and verbally abusive to Ayesha and was controlling of her and their children. Ayesha stayed with her husband for the sake of the children and her family’s izzat (honour).

Ayesha’s first language is Urdu; she speaks very little English. Tariq did not see a need for her to learn. Tariq died two years ago following a short illness. Bilal, Ayesha’s eldest son, moved in with her after Tariq died. Bilal is widowed and has no children. Bilal often tells Ayesha how lucky she is to have a devout son who has come home to look after his mother.

Bilal uses the whole house, apart from her bedroom, as his own. Bilal often yells at her and Ayesha feels in his way in the lounge especially if he is watching television with his friends. She spends most of her time in her bedroom.

Bilal collects Ayesha’s pension and does the food shopping on a weekly basis. He says she deserves to rest, not carry heavy bags on the bus. Ayesha used to enjoy cooking but now she gets stressed in case a meal doesn’t please him. Sometimes he wants a full meal cooked quickly for his friends.

Ayesha is often tearful and is very tired all the time. She has lost weight and is not sleeping. She finds it hard even to pray. This upsets Ayesha as her faith is important to her.

Normally the family visit monthly at the weekend. Recently her daughter Amnam, came to visit unexpectedly. She is worried that Ayesha is having problems with taking care of herself. She says Ayesha needs help to keep clean, wash her clothes and she thinks Ayesha is avoiding drinking too much because getting to the bathroom is difficult for her. Amnam wants Ayesha to have a social care assessment, so that she can have help with personal care from a woman if she needs it. Amnam convinced Bilal, who agreed, providing he could interpret for her.

A social worker, Marhaid, comes to the house with Ali, a social work student who speaks some Urdu. After the meeting Ali convinces Marhaid that Bilal had not been interpreting everything Ayesha said and that they should see Ayesha with a professional interpreter.

How would you make safe enquiry with Ayesha?

Who will meet with her?

Where?

How will you contact her to arrange the meeting?

Assessment

In this section are two downloadable PDFs – one is a partly completed assessment form related to this case study, and another is an example of what a completed form could look like.

Suggested exercise

Download the partly completed assessment as a PDF file (487KB)

Download the completed assessment as a PDF file (487KB)

Use the partly completed assessment form:

- What actions would you discuss with Ayesha to ensure her immediate and longer term safety?

- What precautions would you need to take to avoid putting her at higher risk of harm?

- What is your analysis of the situation? Is coercive control occurring? What is the evidence of this?

- What is your conclusion?

DASH- RIC

Download the blank DASH_RIC as a Word .DOC file (226KB)

The purpose of the DASH risk checklist is to give a consistent and simple tool for practitioners who work with adult victims of domestic abuse in order to help them identify those who are at high risk of harm and whose cases should be referred to a MARAC meeting in order to manage their risk. If you are concerned about risk to a child or children, Safe Lives recommend that you should make a referral to ensure that a full assessment of their safety and welfare is made.

There are two downloads on this page.

One shows a blank DASH risk checklist, with quick start guidance from Safe Lives. The key point is to remember that your professional judgement is key in making a decision about risk; a tool can help, but the score it comes out with is not definitive.

This is especially relevant when working with people with care and support needs, for whom some of the questions may not be relevant.

Download the case study DASH-RIC as a PDF file (211KB)

The other shows an example of a completed DASH relating to this case study, for you to critique and appraise.

Suggested exercise:

- Read the case details and full assessment document for this case study.

- Using the information contained, fill out a blank DASH risk assessment tool.

- Discuss how you found it; did you have all the required information? Would you be able to get all the required information in practice? Would you make a referral to MARAC?

Topics

This section picks out three main topics from the case study featured. For Ayesha’s case study, the topics include:

- Working with Pakistani women and women of Muslim faith

- Intersectionality

- Building cultural capability

A selection of references, tools and further reading for each topic is below.

Working with Pakistani women and women of Muslim faith

‘Women in Pakistan are a diverse group and embrace differences in class, ethnicity, religion, identity and status. Despite these differences there are some common themes which emerge from their narratives. These are primarily centred on patriarchy, family honour and the use of religion (mainly Islam). It is in these arenas that domestic violence continues to be perpetuated as a private matter.’ (Siddique et al, 2008)

This comprehensive research project conducted by Nadia Siddiqui, Sajida Ismail and Meg Allen investigated the complex issues impacting on Pakistani women. The study provides insight into

‘the deeply embedded ‘culture’ of male and familial domination over Pakistani women’ which they conclude is ‘a characteristic not exclusive to poorer uneducated women’ (2008:149)

Working with Pakistani women. Siddiqui N, Ismail S and Allen M (2008) Safe to return? Pakistani women, domestic violence and access to refugee protection – a report of a trans-national research project conducted in the UK and Pakistan. South Manchester Law Centre and Manchester Metropolitan University. http://www.casas.org.uk/papers/pdfpapers/safe.pdf/

Muslim Women’s Network UK (MWNUK) explains that Muslim women experience a range of issues related to domestic abuse.

‘Culture poses a barrier to seeking help because of dishonour, shame, stigma and being rejected by the community. Some women do not feel comfortable contacting local groups because they are often based in the communities in which they live and fear breaches of confidentiality. These women remain isolated and unsupported. A helpline can provide a safe space to talk about problems because callers can remain anonymous.’

The Muslim Women’s Network Helpline can be contacted on 0800 999 5786 or you can visit their website http://www.mwnhelpline.co.uk/

Tool one (below) looks at the principles that underpin good social work practice around religion and belief. You can use the questions in the tool to reflect on your practice.

The evidence scope gives more information on issues which affect specific communities, such as so called honour based violence, which is categorised as a type of domestic abuse in the Home Office Statutory Guidance Framework.

So called Honour Based Violence (HBV) is an umbrella term to encompass various offences covered by existing legislation, including Forced Marriage and Female Genital Mutilation.

HBV can include a collection of behaviours which are used to maintain control within families or other social groups. The risks can be high as there may be many abusers in the extended family or community networks. Other people in the family or community may pressure the victim to return to abusive situations or fail to support them. It is important to understand HBV in the context of violence against women and girls and consider the risks to all women and girls in the family.

Another form of abuse alluded to in this case study is domestic servitude. While it is not covered in the coercive control legislation, it is an offence under the Modern Slavery Act 2015.

CPS guidance on Human Trafficking, smuggling and slavery:

http://www.cps.gov.uk/legal/h_to_k/human_trafficking_and_smuggling/#a07

Intersectionality

Intersectionality refers to how different aspects of identity are interconnected. Theories of intersectionality explain how identity and consequential experiences of discrimination cannot be examined separately from one another, nor by a simple ‘adding up’ of different aspects of oppression. Rather, multiple dimensions combine to intensify (or reduce) systematic and institutional oppression.

You can find out more about intersectionality in slides outlining theories of domestic abuse, and some videos that explore themes of intersectionality are linked to below.

‘In every generation and in every intellectual sphere and in every political moment, there have been African American women who have articulated the need to think and talk about race through a lens that looks at gender, or think and talk about feminism through a lens that looks at race. So this is in continuity with that.’ Kimberlé Crenshaw

Video

Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, Women of the World Festival, 2016, Keynote Southbank Centre (30:46 mins):

Having trouble with the embedded player? Go directly to the video page:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-DW4HLgYPlA&feature=youtu.be

Identity is fluid and multi-faceted. People have multiple identities and while some combinations further disempower, other dimensions might privilege individuals and groups, creating a complex pattern of social relations based on inherent advantage or disadvantage.

Video

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: The danger of a single story:

Having trouble with the embedded player? Go directly to the video page:

https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?language=en (19 mins)

Video

‘What is privilege?’ (3:55 mins – via YouTube)

Having trouble with the embedded player? Go directly to the video page:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hD5f8GuNuGQ

Intersectionality explains how ‘abusers’ might gain power across a number of dimensions for example a non-disabled British adult male in an intimate relationship with an EU migrant female with restricted mobility (see case study 4 Maria)

There is significant evidence that people with care and support needs are more vulnerable to domestic (& other forms of) abuse AND less likely to have access to the services and the protection that may be needed.

You can find further evidence and information in Case Study Maria (see Case Study Maria Topics, Case Study Emma Topics, also Additional resources and Evidence scope)

In conclusion,

- There is a long history of domestic violence, victim blaming and of justifications for the male abuse of women.

- Domestic abuse in essence is a gendered crime, it is about the misuse of power vested in the cultural identity given to males

- Alongside gender identity those of religion or belief, race, age, sexual orientation, disability and other dimensions of oppression are also important. When several of these interconnect unfavourably in a person’s identity – the person becomes more vulnerable to abuse. Feminist theories of intersectionality explore the interaction of multiple identities and female subordination.

- Tool 2 supports reflection on professional knowledge. It outlines a number of reflective questions which can be used with a specific case in mind. These questions can help to clarify unconscious biases and work out what is influencing professional judgements.

Building cultural capability

Two mnemonic models offer a framework for the continuous development of cultural capability, seeing this as an essential and ongoing process of good social work practice:

Campinha-Bacote’s ASKED model of building awareness, skills, knowledge, encounters and a desire to develop cultural competence.

Carballeira’s LIVE and LEARN Model whereby practitioners like, inquire of, visit and experience people from different ethnic groups in order to listen, evaluate, acknowledge, recommend and negotiate approaches which are the most culturally acceptable (Carballeira, 1996 in Laird, 2008).

Explore these models in Tool 3, below.

You can use the guide:

Assessing Social Work practice against the PCF: Principles for gathering and using feedback from people who use services and those who care for them. The College of Social Work in the Professional Development section

to help you in routinely gathering feedback to support your ongoing development of cultural capability.

Tools

- Tool 1: Principles for reflection on religion and belief

This tool sets out the principles that underpin good social work practice around religion and belief. You can use the questions below to reflect on your practice.

- Tool 2: Reflection on our ways of knowing

‘This tool supports reflection on professional knowledge. It outlines a number of reflective questions which can be used with a specific case in mind. These questions can help to clarify unconscious biases and work out what is influencing professional judgements.’

- Tool 3: Building cultural capability

‘This tool outlines a framework for developing cultural capability, seeing this as an essential and ongoing process of good social work practice. Drawing on Carballeira (1996), it explores what social workers and social care practitioners need to do to develop their cultural capability.’

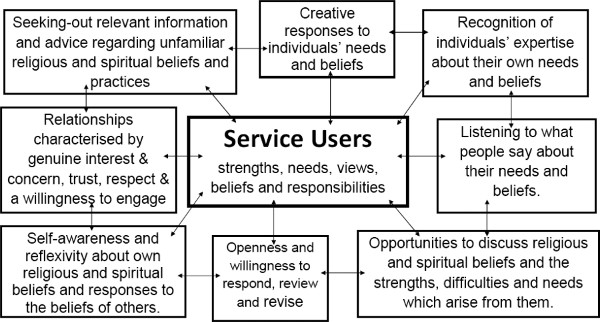

Tool 1: Principles for reflection on religion and belief

Download the tool as a PDF file

This tool sets out the principles that underpin good social work practice around religion and belief. You can use the questions below to reflect on your practice.

- Are you sufficiently self-aware and reflexive about your own religious and spiritual beliefs or the absence of them and your responses to others?

- Are you giving the individuals/ groups involved sufficient opportunities to discuss their religious and spiritual beliefs and the strengths, difficulties and needs which arise from them?

- Are you listening to what they say about their beliefs and the strengths and needs which arise from them?

- Do you recognise individuals’ expertise about their own beliefs and the strengths and needs which arise from them?

- Are you approaching this piece of practice with sufficient openness and willingness to review and revise your plans and assumptions?

- Are you building a relationship which is characterised by trust, respect and a willingness to facilitate?

- Are you being creative in your responses to individuals‟ beliefs and the strengths and needs which arise from them?

- Have you sought out relevant information and advice regarding any religious and spiritual beliefs and practices which were previously unfamiliar to you?

This tool is based on Furness S and Gilligan P (2010) Social Work, Religion and Belief: Developing a Framework for Practice, British Journal of Social Work, 40 (7), pp 2185-2202.

Text of the diagram (clockwise)

Clockwise:

- Seeking out relevant information and advice regarding unfamiliar religious and spiritual beliefs and practices

- Creative responses to individual's needs and beliefs

- Recognition of individuals' expertise about their own needs and beliefs

- Listening to what people say about their needs and beliefs

- Opportunities to discuss religious and spiritual beliefs and the strengths, difficulties and needs which arise from them

- Openness ad willingness to respond and revise

- Self-awareness and reflexivity about own religious and spiritual beliefs abnd responses to the beliefs of others

- Relationships characterised be genuine interest and concern, trust, respect and a willingness to engage

Centre:

Service Users

strengths, needs, views, beliefs and responsibilities

[_/su_spoiler]

Tool 2: Reflection on our ways of knowing

Download the tool as a PDF file

This tool outlines a framework for developing cultural capability, seeing this as an essential and ongoing process of good social work practice. Drawing on Carballeira (1996), it explores what social workers and social care practitioners need to do to develop their cultural capability.

This tool supports reflection on professional knowledge. It outlines a number of reflective questions which can be used with a specific case in mind. These questions can help to clarify unconscious biases and work out what is influencing professional judgements.

The deconstruction of professional knowledge

‘We are socialized into ‘ways of looking’ which render some things visible, others invisible. These ways of looking are so tacit, so habitual and automatic that they themselves are rarely the topic of conversation. The problem when we try to explain to others what we see is that we tend to assume that what we see, or what we know, is obvious to anyone who ‘looks at the facts’. But there are no neutral facts waiting to be seen. It is only when one knows how to look, that the facts relevant to that way of looking appear. Opening our ways of knowing to inquiry is not unlike the challenge of trying to explain to someone how to look in such a way that they can see that third dimension.’

Reflection on our ways of knowing

‘This kind of reflective engagement with our knowledge commits us to reflection not just upon what we think, but also upon how we came to think that way, not just upon what we know to be so, but also upon how we know it to be so. It asks that when we speak of what we know we also add ‘This is how I came to see it in this way. These are the assumptions I make and the values which I know influence my orientation to the world. This is what I see when I look this way.’ Our knowledge is presented not as an authoritative finished product (‘These are the facts’), disembodied from our way of being in the world, but as a possible expression of the place we occupy in our world. This does not preclude the possibility of being able to say with clarity or commitment what we know. The difference is that we attempt to locate our knowledge as our own and seek to make visible the process of coming to know that which traditional scientific discourse would render invisible.’

Reflective questions

Reflection on the sources of our knowing may lead us to ask ourselves the following kinds of questions:

What frames of mind am I bringing to this situation? (e.g. what are my initial thoughts and explanations for the situation?)

What am I taking to be the facts of this situation?

Why did I orient to these particular facts rather than others?

What am I not seeing in this situation?

Would someone whose gender, social location, professional doctrine or culture is different to mine orient differently to this situation?

Where did I learn this ‘way of looking’?

Whose voice is being exercised in this knowledge? Is it mine, or someone else’s?

What are the cultural, gender or epistemic[1] biases implicit in this way of looking?

Is my own experience represented in this knowledge?

Is there some personal experience which is silenced by this knowledge?

Do I recognise myself and my experience in this way of speaking my knowledge?

References

Sellick, M., Delaney, R. and Brownless, K. (2002) ‘The Deconstruction of Professional Knowledge: Accountability without Authority.’ Families in Society Vol. 83(5), pp.493-498.

[1] Epistemic - of or pertaining to knowledge or the conditions for acquiring it. From the Greek ‘epistemology’ (knowledge, science) - theory of knowledge or the branch of philosophy concerned with the nature and scope (limitations) of knowledge. It addresses the questions:- What is knowledge?

- How is knowledge acquired?

- How do we know what we know?

Tool 3: Building cultural capability

Download the tool as a PDF file

This tool outlines a framework for developing cultural capability, seeing this as an essential and ongoing process of good social work practice. Drawing on Carballeira (1996), it explores what social workers and social care practitioners need to do to develop their cultural capability

Two mnemonic models offer a framework for the continuous development of cultural capability, seeing this as an essential & ongoing process of good social work practice:

Campinha-Bacote's ASKED model of building awareness, skills, knowledge, encounters and a desire to develop cultural competence

Carballeira’s LIVE and LEARN Model whereby practitioners like, inquire of, visit and experience people from different ethnic groups in order to listen, evaluate, acknowledge, recommend and negotiate approaches which are the most culturally acceptable (Carballeira, 1996 in Laird, 2008).

You can use the guide:

‘Assessing Social Work practice against the PCF: Principles for gathering and using feedback from people who use services and those who care for them’.

The College of Social Work in the Professional Development section

to help you in routinely gathering feedback to support your ongoing development of cultural capability.

Building cultural capability

Carballeira’s LIVE and LEARN Model (Carballeira, 1996 in Laird, 2008).

This tool outlines a framework for developing cultural capability, seeing this as an essential and ongoing process of good social work practice.

Social care practitioners need to:

Like – develop a liking for work with people from minority communities.

Inquire – commit to finding out about diverse ethnic groups.

Visit – be a respectful and observant visitor when working with people from other ethnic groups.

Experience – seek out social interactions with people from other ethnic groups

Listen – observe style used by people from different communities & adopt styles of communication.

Evaluate – recognise everyone integrates culture and personality in individual ways and avoid stereotyping

Acknowledge – identify similarities and differences and any areas of potential conflict with statutory requirements and inform the service user.

Recommend – offer service users a range of intervention approaches and consult on which are most culturally acceptable.

Negotiate – openly discuss areas of conflict & work towards acceptable compromises.

You can use the critical reflection tool and action planning tool to review your ongoing progress in developing cultural capability.

You can use the principles of gathering feedback tool to structure how you routinely gather feedback on your practice from people who use services and those who care for them.

Also see the diagram below illustrates the stages that people move through in developing cultural competence.

‘Moving towards cultural competence’ (Carballeira, 1996, in Laird, 2008)

Stages (from left to right):

Superiority –the practitioner believes that the service-user’s culture is inferior and attempts to impose his or her values and worldview.

Incapacity – the practitioner recognises that there are cultural differences, but has no skills to address them and therefore offers a standard intervention based on the dominant culture.

Universality – the practitioner believes that all human beings share the same fundamental values and therefore treats all service-users and carers alike.

Sensitivity – the practitioner recognises cultural differences, particularly around language, and makes an effort to address these within an essentially standard intervention.

Competence – the practitioner identifies, respects and incorporates the values of the service-user in the design and delivery of the service.

[_/su_spoiler] [_/su_accordion]References

Carballeira, N. (1996) in Laird, S. (2008) Anti-oppressive social work: A guide for developing cultural competence. London: Sage

Crenshaw, K (1993) Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics and violence against Women of Color. Stanford Law Review, 43, 1241.

McGarry J and Simpson C (2011) Domestic abuse and older women: exploring the opportunities for service development and care delivery. The Journal of Adult Protection, 13, 6, 294-301.

Siddiqui N, Ismail S and Allen M (2008) Safe to return? Pakistani women, domestic violence and access to refugee protection – a report of a trans-national research project conducted in the UK and Pakistan. South Manchester Law Centre and Manchester Metropolitan University. http://www.casas.org.uk/papers/pdfpapers/safe.pdf/

The College of Social Work (undated) PCF20: Assessing Social Work practice against the PCF: Principles for gathering and using feedback from people who use services and those who care for them. TCSW

Waheed, A (2015) British Muslim Women’s helpline: Their voices won’t go unheard again. The Telegraph. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/mother-tongue/11341201/British-Muslim-women-and-girls-have-an-advice-helpline-at-last.html